How I avoid getting blindsided by stakeholders

Anticipate questions and concerns to de-risk your work and showcase your competence

👋 Hi, it’s Torsten. Every week I share actionable advice to help you grow your career and business, based on operating experience at companies like Uber, Meta and Rippling.

P.S. If you enjoyed the post, consider sharing it with a friend or colleague 📩; it would mean a lot to me. If you didn’t like it, feel free to send me hate mail.

You can’t perfectly predict what’s going to happen; if you could, you’d be playing the lottery or day trading on Robinhood instead of reading this.

But that’s not an excuse for not looking forward at all. Over and over, I’ve seen people be surprised by questions or concerns from stakeholders that they could have easily anticipated (and frankly, it’s happened plenty of times to me as well).

And it’s a costly mistake to make:

Being stumped by a seemingly simple question can derail an entire presentation, and unexpected pushback from another team can block your launch at the last minute.

I’ve learned this lesson the hard way myself, and put together this post so you can learn from my mistakes.

By anticipating questions and concerns, you can 1) improve the odds of success of whatever you’re doing and 2) develop a reputation for being competent and diligent.

And it only takes a bare minimum level of effort.

In this post, I will cover:

Why you should prevent surprises

How to anticipate questions and concerns

3 real life examples of how this will help you stand out

Let’s get into it.

Why you should prevent surprises

De-risking your work

One of the early big projects I worked on at UberEats was a change to delivery pricing. As part of this launch, we planned to send a message to all drivers in the affected markets (including those on Uber Rides, because they were able to do deliveries).

To me, this was just an item on the check list: “Pull list of drivers and send email”.

If I had taken the time to think through it, however, I would have realized that the Rides team might have some predictable questions and concerns; for example:

🤔 “Why do we have to message all drivers? Since this is a delivery-specific pricing change, can’t we narrow down the target audience?”

📅 “Can we postpone this announcement by a week? There is another important message going out and this might distract from it".”

I was able to address these concerns and proceed with the launch and comms on the planned timeline, but it certainly didn’t help me build trust with my cross-functional partners (and it almost derailed my launch).

Don’t let that happen to you; I definitely learned my lesson from this and make sure nowadays that I’m anticipating these kinds of things in advance.

Doing this will help you:

Avoid working on things that were doomed from the start

Avoid bottlenecks or delays by addressing concerns from stakeholders early on

Build trust with your stakeholders by showing that you considered the impact of your work on the broader organization

Establishing competence

If you want to be viewed as competent and diligent, you need to show that you deeply understand the topic you are working on and that you have thought through every important aspect.

This requires preparation, especially for live presentations. If someone asks a question, you won’t have time to deeply think about it or do an investigation — so you need to figure out in advance what questions stakeholders will likely ask.

Why is this so critical?

If your audience asks a question or challenges your plan and you are well-prepared, you give the impression that you “thought of everything”

On the other hand, if you are struggling with a simple question, people will wonder: “They should know this. What else did they not think through? How robust can this analysis or plan be?”

Once you’ve lost people’s trust because you were unprepared, it’s hard to win it back. So let’s dig into how you can prevent that from happening 👇

How to anticipate questions and concerns

It’s difficult to anticipate things without a structure. There is an infinite number of things that could happen, so where do you even start?

There are a couple of techniques that have helped me do this in practice:

🤗 Use empathy

If you put yourself into the shoes of someone seeing your deliverable or hearing your presentation for the first time, you can anticipate some of the questions or concerns they might have.

To do this, think back to when you started working on the topic:

What were the questions you asked yourself?

What misunderstandings did you have initially? What took some time until it “clicked”?

Whatever was on your mind at the beginning is likely what others are wondering about as well.

🎯 Understand other teams’ priorities

It’s much easier to anticipate what people might ask or be concerned about if you understand what they care about.

Ultimately people are selfish; so when they are listening to your presentation or reviewing your proposal, they are constantly wondering “How does this affect me?”.

To get a better idea of other team’s priorities, you can:

Review their planning docs and roadmaps

Attend business reviews and cross-functional syncs

Do 1v1s and coffee chats with people on other teams

Talk to your manager; they will typically have a good overview of what each team is working on

Once you understand what is top of mind for others, you can anticipate what their reaction to your work will be.

🐷 Use a guinea pig

Sometimes it’s hard to “forget” all of the expert knowledge you have.

To get truly representative input, present your work to someone who has no context (e.g. a colleague on your team who is working on something completely different).

Ask them to repeat back to you what they understood; this will tell you which parts didn’t come across clearly (or weren’t highlighted enough).

😈 Play devil’s advocate

Pretend that it’s your job to poke holes in your own work and that you’ll get a reward for every weak spot you find:

What are the weakest assumptions you made? Where were you the most optimistic?

What’s most likely to go wrong with this proposal?

What arguments don’t flow logically?

Doing this will feel painful, but it will prepare you for the worst case scenarios (and any colleague that might try to derail your project).

🧠 Draw from experience (yours and others’)

I’d estimate that more than 90% of the questions and concerns that come up at work are not new — rather, the same topics come up over and over again.

Why is that? Because people’s priorities don’t change that often.

For example, when I worked on the Growth team at Rippling, Sales always cared about 1) how many opportunities we would generate for them and 2) what the quality of these opportunities was.

No matter what we did, they would be worried that it would result in fewer opportunities coming their way, or that the mix would shift to lower-quality channels.

Knowing this allowed me to preempt their concerns whenever we presented a plan or proposal.

Keep track of the questions different people ask. Does the CFO always ask about how much things will cost? Does the BizOps team always ask whether it will affect the forecast?

Use the 80/20 rule

While you should do your best to anticipate the most likely questions or concerns, you realistically can’t be prepared for every scenario.

This is a good example of the 80/20 rule. If you keep track of the questions people ask or the reasons they push back on proposals, you will notice that a few recurring topics make up 80% of the volume.

Covering your bases by addressing these “high-likelihood” issues is a very good use of your time — trying to anticipate every possible question or concern is not.

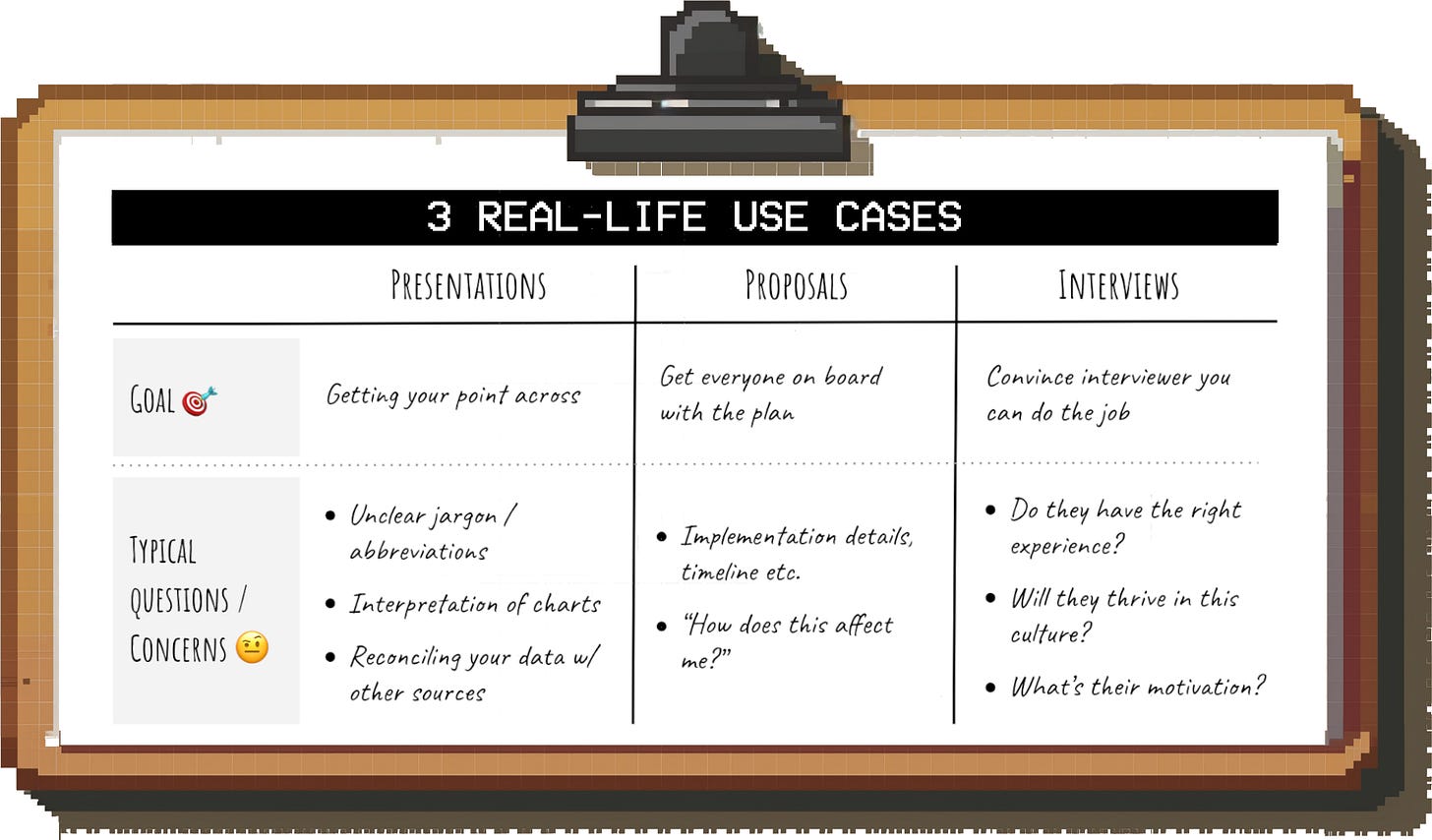

3 real-life use cases for anticipating questions and concerns

👩🏫 Use case 1: Presentations

The goal: Making sure you get your message across.

What to anticipate:

A presentation is not a monologue. Often, it turns into a discussion as the audience asks questions.

This “interactive” portion of the presentation should not be an afterthought — how you handle the questions is arguably even more important than the content you share.

Typical questions you can expect:

“What does this mean?”: You should be prepared to explain every single term or abbreviation you use in your presentation.

“How do I read this chart?”: People often struggle to correctly interpret charts on the spot, esp. if they are more complicated (e.g. multiple axes). Be prepared to walk people through how to make sense of them.

“Do you have this data by [product / marketing channel / country / etc.]”?: If you present data, you should expect that people want to see a different or more detailed cut.

“This number is different from what I saw the other day”: When you present information, people will compare it against what they already know. Make sure you check what other material exists on this topic (e.g. other presentations, dashboards showing similar data etc.) and can explain any discrepancies.

“Why did you decide to do X?”: You should always be prepared to explain why you or your team made certain choices (e.g. pick a certain market, roll out a feature only to certain users, choose an experiment design etc.]

How to stand out:

Bare minimum: Obviously, you should have an answer to the most likely questions people might ask. If you expect a question but don’t know the answer, find it before the presentation.

Next level: If you want to knock things out of the park, put supporting data that directly addresses expected questions in the appendix. This shows that you thought through the issue in advance and builds trust that you’re “on top of things”. Plus, it will make your life much easier if you struggle to explain things on the spot.

📝 Use case 2: Proposals (new feature, launch, marketing campaign etc.)

The goal: Making sure everyone is on board with the plan.

What to anticipate:

No matter how good your proposal is, most people will be skeptical rather than excited. They are working on their own things and are worried that whatever you’re doing will make their lives harder.

Your job is to address their concerns and get them bought into the plan.

Typical questions or concerns you can expect:

Questions about the specs, implementation, timeline etc.: Be prepared to explain what exactly is happening and by when. If something is still up in the air, clearly say so and tell people by when it will be decided.

“How does this affect me?”: Based on each team’s priorities, you should be able to anticipate what they’re worried about. For example:

Sales: “How does it affect lead / opportunity volume and quality?”

Finance: “How much does this cost / how does it affect the budget?”

Data Science: “What do we need to measure / how does this affect existing experiments?”

BizOps: “How does this affect the forecast / goal attainment?”

Support: “When will this launch? Where can we find documentation to train support agents?”

How to stand out:

Bare minimum: Be as transparent as possible and share the key information other teams might care about. E.g. when you propose a new Marketing campaign and Finance will review the plan, show where the funds will be coming from, what the expected spend and efficiency will be etc.

Next level: If you want to really set yourself apart, create an FAQ section in your plan:

💼 Bonus use case: Job interviews

The goal: Removing any doubt in the interviewer’s mind that you can do the job.

While most of this article focuses on anticipating questions or concerns on the job, the same approach can be used in an interview setting to preempt any concerns the interviewer might have.

What to anticipate:

A good interviewer will have read your resume and have a list of questions they want to resolve during the interview. However: They will rarely state these out loud.

For example, if you are applying for a position that is looking for more years of experience than you have, they will want to understand if you’re ready for that level of responsibility and scope. But most likely, they won’t confront you with this concern directly.

Typical interviewer concerns you can expect:

Experience: “Has this person done this before? Do they have enough experience?”

Culture: “Will they thrive in this culture?” (e.g. scrappy startup vs. Big Tech)

Motivation: “Why do they want to leave their current role? Why is this person applying for an IC role if they’ve been a manager before?”

How to stand out:

Reflect on your “weak spots” compared to the job description, and directly address them. It might feel uncomfortable to bring this up proactively, but it shows introspection and gives you a chance to control the narrative.

As a hiring manager, I prefer a person that lacks experience but is self-aware and coachable over someone who is trying to oversell their experience any day.

For example, if you’re an Individual Contributor applying for a position that requires hiring and managing a few people, you can say:

✅ “The player-coach nature of the role is ideal for me. I haven’t formally managed a team in the past, but have led large cross-functional project teams and mentored the junior analysts on the team — so this feels like a natural next step.”

Remember: The interviewer already knows if you lack a certain experience they are looking for, and addressing the topic allows you to explain why it won’t prevent you from succeeding in the role.

Closing thoughts

Way too many times I’ve seen people get stumped by obvious softball questions during presentations, or projects get blocked because concerns from other teams were not taken into account.

In many cases, that was avoidable. Most people’s thought processes are predictable once you know what they care about, so take advantage of that.

It’s one of the easiest ways to stand out and demonstrate your competence.

Love the call out to use empathy to anticipate questions and concerns. I've found that it's especially useful to put yourself in the shoes of the people who you'll be communicating to.

Head of cloud? Frame it in cloud savings/costs, uptime.

Head of product? Frame it in revenue.

Head of customer success? Frame it in retention, reducing churn, increasing LTV, etc.

And so on.