The power of incentives

How to get people to do what you want without micromanagement

Cleverly designed incentives are the (hidden) driver behind some of the biggest growth success stories such as Dropbox’s explosive user growth in its early years.

In addition, incentives are often the reason for outstanding employee productivity (when designed right) or organizational dysfunction (when designed poorly). That constant clash between Marketing & Sales? The frustration you have in working with the Legal team?

All because of misaligned incentives.

In fact, I’d argue that incentives are one of the most underrated lever companies have at their disposal, both for user-facing work as well as internal management.

In this post, I will cover:

Why incentives matter

How to set incentives

What it looks like when incentives are working

Where incentives create problems and what to do about it

Let’s dive in.

Why Do Incentives Matter?

At Uber, my focus for years was managing incentives to balance the marketplace.

We would design incentive schemes like “Do 10 trips in this area and get an extra $50” to motivate drivers to go online and move to areas where they are needed the most.

Marketplaces like Uber do this because they don’t directly control the supply side. It’s in Uber’s interest that enough drivers are online in a given place at a given time, but since they are independent contractors and not employees, Uber cannot instruct them to show up.

The same applies when you’re trying to get your prospects, customers or users to do something: You have no direct control over their actions, so you need to create the right conditions and motivate them to take certain actions.

But it goes beyond that: Even in employment relationships (at least in Tech), we have largely moved away from micromanagement and directly overseeing a person’s every action and task. Even if we wanted to (which a lot of us don’t), we can’t due to hybrid and remote work.

Instead, managers’ job is now to create the conditions that:

Employees can do their jobs (coaching, connecting, unblocking etc.) and

They will do the right things (this is where incentives come into play)

The thinking is: If you set the right incentives and get out of people’s way, they will act entrepreneurially and find creative ways to hit their goals and benefit the company.

Every manager wants their team to “act like owners”, but people are inherently selfish. By setting incentives so that their goals align with those of the company you can get what you want without having to change fundamental human nature.

I’m not the first one to appreciate the importance of incentives. Adam Smith wrote in “The Wealth of Nations” in 1776 that you get people to do things by appealing to their self-interest, and when I was in grad school, one of my Finance professors said:

“Every company should have a Chief Incentive Officer.” - Prof. Robert C. Merton, Nobel Laureate and Professor of Finance at MIT

In reality, almost no company does. In addition, incentive design is not really a focus in neither college nor on-the-job training, so most of us are not familiar with it.

As a result, incentives are often poorly designed; I would even go so far as to say that many of the biggest problems in companies can be traced back to poor incentive management.

So what can we do about it?

How to set the right incentives

Setting incentives is all about:

Defining a clear goal

Setting a target for the actor(s) you are trying to influence

Tying an attractive incentive to hitting that target

Step 1: What goal are you trying to achieve?

To design the right incentive, you need to be clear on the ultimate business outcome you are trying to achieve.

In the absence of a goal, people will typically start focusing on whatever is 1) easiest for them to measure and 2) easiest to move.

For example, if you don’t give your Marketing team a goal, they’ll likely start optimizing for impressions since 1) the data is easily available in near-real-time and 2) it’s easier to get eyeballs on something than to actually convert those impressions into down-funnel outcomes.

Setting a clear goal is the foundation for everything that follows.

Step 2: Set a target for the actor(s)

Once you’re clear on what business outcome you want to achieve, you need to figure out:

Who needs to take action, and

What actions you want them to take

In other words, you need to 1) translate the qualitative business goal into a measurable metric, 2) set a target against this metric, and 3) assign an owner that is responsible for hitting this target.

At first glance, this might seem straightforward. For example, if you’re Uber and want to grow revenue, you could give your Driver Ops managers a target to grow trip volume and they will work to get more drivers online, which will improve match rates and result in more trips.

Unfortunately, things are not that simple.

Minimizing adverse consequences

Well-intentioned targets can quickly lead to unintended consequences.

In the example above, there are two key issues:

1. The target incentivizes behavior that will not maximize value for the business

The easiest way to grow trips on the Uber platform is to focus on low-value, high-volume products like UberPool and UberX. The most profitable, and thus valuable, trips for Uber, however, are those on premium products like UberBlack (or specific types of trips like airport trips).

So if you want to maximize value for the company, you either need to couple the trips target with a target margin (so that Operations Managers have to also focus on growing premium products), or choose a metric that takes both trip volume as well as the value of a trip into account, like Bookings (the $ value of all trips).

Read more on how to design good metrics and prevent people from gaming them here.

2. The desired business outcome is not under the control of a single person or team

Let’s consider the Uber example again. You can achieve some growth by incentivizing the Driver Ops managers to grow supply in the marketplace. However, at a certain point, you have enough drivers and are fulfilling almost every trip request that comes in.

At that point, to grow further, you need to also grow the demand side. To do that, you can give a target to the Rider Growth team to grow trip requests.

The key here is to ensure the incentives are in sync.

✅ Giving both teams growth targets makes sure they pull in the same direction.

❌ Giving one team a target focused on growth and another one focused on financial efficiency, on the other hand, would result in friction.

Step 3: Create an incentive to hit the target

Once you’ve set targets for the relevant actors, you need to create incentives to ensure they work hard to hit them. People are selfish, after all.

Anything that people find valuable can be an incentive. The key levers you have at your disposal can be summarized as:

💰 Money: A lot of incentives are of monetary nature. This includes cash as well as other things of monetary value like equity, $ credits in a user wallet, gift cards etc.

⚙️ Utility: You can offer non-monetary things that people find valuable, e.g. unlocking features in a product

🌟 Recognition: It doesn’t always have to be expensive. (Public) Recognition can be a powerful motivator in some situations (e.g. a public shout-out at the company all hands)

🚀 Opportunity: Access to opportunities is valuable, so people are willing to work for it. E.g. people take on a difficult additional project or work hard to hit an ambitious target since it will typically increase odds of a promotion.

One incentive type is not necessarily better than the others. People place very different weights on these categories, so you have to understand what your team / customers / users etc. value the most (and what’s easiest for you to provide).

The magic of aligned incentives in practice

When incentives are perfectly aligned, it’s like magic.

Consider companies with same-side network effects. These are products or services where adding more users increases the value the product/service brings for each user.

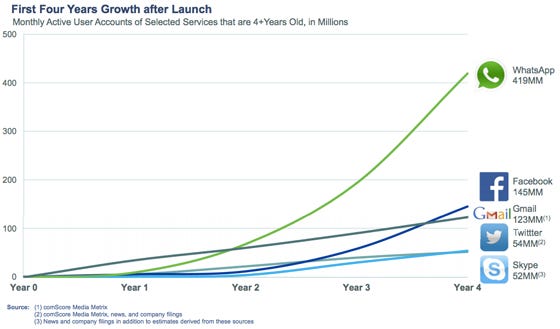

Let’s take WhatsApp as an example. Their impressive user growth from 0 in 2009 to ~500M when they were acquired by Facebook in 2014 was all organic. Like basically every other WhatsApp user, I was convinced by my friends to download the app.

Why did my friends bother to do that? Because having all of their friends on WhatsApp made the app much more useful.

The incentives were perfectly aligned: WhatsApp wanted more people to use the app, and so did every single one of their users.

Not every company has network effects this strong, though. That’s where incentive schemes come into play:

Dropbox becomes somewhat more useful if other people you know use it, but not as much as a messaging service. So in order to entice users to recruit their friends, Dropbox had to offer an incentive.

In 2012, Dropbox launched the Space Race, focused on schools. The deal was simple: Every user who participates gets 3 GB of free storage, plus more storage depending on how many referrals the school achieves.

This way, incentives were aligned: As an existing Dropbox user, I’m incentivized to refer as many people as possible.

People have a reason to accept the referral because they get 3 GB of free space instantly, and they also have a reason to then help generate more referrals to hit the school-level goals, benefitting everyone.

And Dropbox didn’t have to offer $$$ to achieve this, just extra utility in the product.

Consequences of misaligned incentives

Although aligned incentives can create smooth flywheels like the ones discussed above, in reality, incentives are often misaligned between parties.

Let’s look at some common examples and how they can be fixed.

👨👩👦👦 Misaligned incentives between teams

Incentives misaligned between: Different teams in the same company

Example #1: Marketing & Sales Alignment

Incentive issue: Marketing is often measured by how many leads they generate, while Sales is held accountable to closing revenue. As a result, Sales will often complain that the leads Marketing delivers are of low quality and don’t allow them to hit their targets.

What to do about it: Either instead of or in addition to a leads goal, Marketing should take on a target w.r.t. the Pipeline they generate (i.e. the $ value of deals that reach a certain stage in the funnel). A Pipeline target ensures that Marketing is 1) incentivized to generate leads that are of sufficient quality to progress through the funnel and 2) focuses on generating larger deals.

Example #2: Biz <> Legal

Incentive issue: In many companies, the main “feedback” the Legal team gets is that they get in trouble when the company gets sued. As a result, they try to block any business initiative that seems remotely risky.

What to do about it: Hold the Legal team accountable for the risk profile they create for the company and the business impact of their recommendations instead of disciplining them for any legal exposure or lawsuit. At Uber, the Legal team was an incredibly pragmatic partner as their job was to work with the business teams to find the least risky solution to a problem, not eliminate risk altogether. If they shut down an initiative completely, they had to justify that the expected legal risk outweighed the lost benefits to the business.

📋 Company policies that create misaligned incentives

Incentives misaligned between: Company and managers or employees

Example: Expense policies

Incentive issue: Companies want employees to save money when traveling, but employees are incentivized to book the nicest hotel they can within the allowed budget (or fly with their favorite airline even if it’s more expensive)

What to do about it: Share cost savings with employees; i.e. if they stay below the maximum allowed amount per flight / night, give them X% of the difference. There are several companies offering this type of product, but I haven’t seen it widely adopted.

📝 Misaligned incentives in the employment relationship

Incentives misaligned between: Principal & agent (e.g. company & employee)

Example #1: Eliminating your own job

Incentive issue: Employees often find ways to automate parts or all of their job. Unfortunately, many employers would react by laying off these employees as they are “not needed” anymore. As a result, employees are incentivized to simply keep doing their job “as is” without implementing efficiency improvements.

What to do about it: Create a culture where people are incentivized to eliminate their own job. Reward employees who find efficiency gains like this and give them a new, more exciting scope rather than laying them off. The kind of person that finds solutions like this has transferable skills they can apply to many problems.

Example #2: Fixed pay

Incentive issue: Employees that are mostly paid via a fixed salary are incentivized to do the bare minimum to not get fired since their pay is not tied to their effort

What to do about it: Make equity a meaningful part of the overall compensation so that the employee has “skin in the game” (this might be common for engineers in Silicon Valley, but equity is much less meaningful for non-Eng roles and in more traditional companies).

Example #3: Hourly pay

Incentive issue: If you pay someone by the hour, they are incentivized to take longer to complete the task.

What to do about it: If you cannot supervise their productivity and the output is somewhat commoditized, negotiate success-based pay. I.e. it’s fine to pay a financial advisor by the hour because you spend the hour face-to-face getting advice, but if you hire a lawyer online to draft terms & conditions for your startup, pay them for the deliverable.

💰 Business models with misaligned incentives

Incentives misaligned between: Company and user / customer

Example: Ads-based products

Incentive issue: Products or services that run ads make more money the more ads they show, but user experience degrades as a result. They are acutely aware of this trade-off and crank up ad frequency right to the point where the incremental revenue gets outweighed by decreased user engagement / increased churn.

What to do about it: Unfortunately, there is no practical solution. A revenue share with users would align incentives, but ad revenue per user is too low for that to be meaningful. As long as users are willing to put up with ads to avoid paying for a service, it will remain a common and profitable business model.

Closing Thoughts

Incentives are powerful. When used right, they can ensure your users, customers or employees are doing the right things without the need to supervise their every move. Setting incentives and getting out of the way is much more efficient than micromanagement.

Incentives are there, whether you actively put them in place or not; but to reap the full benefits, you need to treat them as an important part of your toolkit and design them intentionally.

Thanks Torsten! Enjoyed the read.

Reminds me of a quote by Charlie Munger, “Show me the incentives, and I'll show you the outcome.”

Learned alot, thanks!

Crazy incentives leads to crazy results. 2008 housing crisis is one of the best examples from history but there is more. I loved the way the information is presented. Clear, explained with enough professional terms without being overwhelming.