How to be "high agency" at work

Practical examples of how to "just do things" when others are stuck overanalyzing and procrastinating — incl. how to leverage AI

👋 Hi, it’s Torsten. In this newsletter, I share actionable advice to help you grow your career and business, based on operating experience at companies like Uber, Meta and Rippling.

If you enjoyed the post, consider sharing it with a friend or colleague; it would mean a lot to me. If you didn’t like it, feel free to send me hate mail.

Over the years, I’ve realized that there’s one single trait that has outsized influence on someone’s level of impact at work. It’s not raw intelligence, and neither is it “people skills”.

It’s probably best illustrated with an example. Let’s say a manager has a small team with two people on it, Hannah and Lance. A new project comes up, and the manager asks Lance to own it. He agrees. A few days later, the manager checks in and asks Lance how he’s progressing. “I was waiting to get more clarity”, he says. “I didn’t really know where to start. What should I do? Who should I loop in? Can we scope this out together?”

The manager agrees, and they spend an hour putting a high-level project plan together.

When Lance comes back a week later with a “project update”, the manager hopes that he has some progress to share. Instead, he brings a list of questions. He is unfamiliar with a part of the project and asks if someone else can handle it instead. He describes three different approaches and asks which one the manager prefers. He’s wondering if the project timeline can be pushed out because he’s waiting to hear back from a key stakeholder.

The project continues like this. The only progress, it seems, is made during the live working sessions the manager and Lance have together.

Frustrated, the manager assigns the next project to Hannah. He mentally prepares himself for a similarly painful process; after all, Hannah has less experience than Lance. But he’s shocked to find that the opposite is true.

Day 3: Hannah sends a message that she put together a working group, identified a similar project that’s running in parallel, and is working with the respective team to deduplicate efforts

Day 7: She gives a brief summary of how they decided to proceed, and says they’ll continue unless there are any concerns

The week after: The manager gets an excited message from another team lead. Instead of writing a lengthy doc and holding endless meetings to debate what to build, Hannah whipped up a prototype so people could react to something tangible. They’re asking if this can be the default approach from now on.

After the project is done, other teams start approaching the manager to ask if he can staff Hannah on their work streams as well. The manager wishes he had more than one Hannah on the team; but since he can’t clone her, he at least puts her up for promotion so she doesn’t leave.

What happened? Is Hannah smarter than Lance? Did she work longer hours? Not necessarily. The main difference is that Hannah has agency.

A brief primer on agency

If you have access to the internet, you’ve probably heard of the concept of agency by now. But in case you haven’t, let’s briefly discuss what it is. There are many definitions out there, but I think about it like this:

(High) Agency is the belief that you can shape your circumstances and achieve your goals through your own actions, rather than waiting for ideal conditions — and the ability to follow through on this belief.

In simpler terms: You think you can make things happen, and then you find ways to make them happen.

It’s kind of the Silicon Valley version of manifestation; but instead of waiting for the universe to make things go your way, you just go and do it yourself.

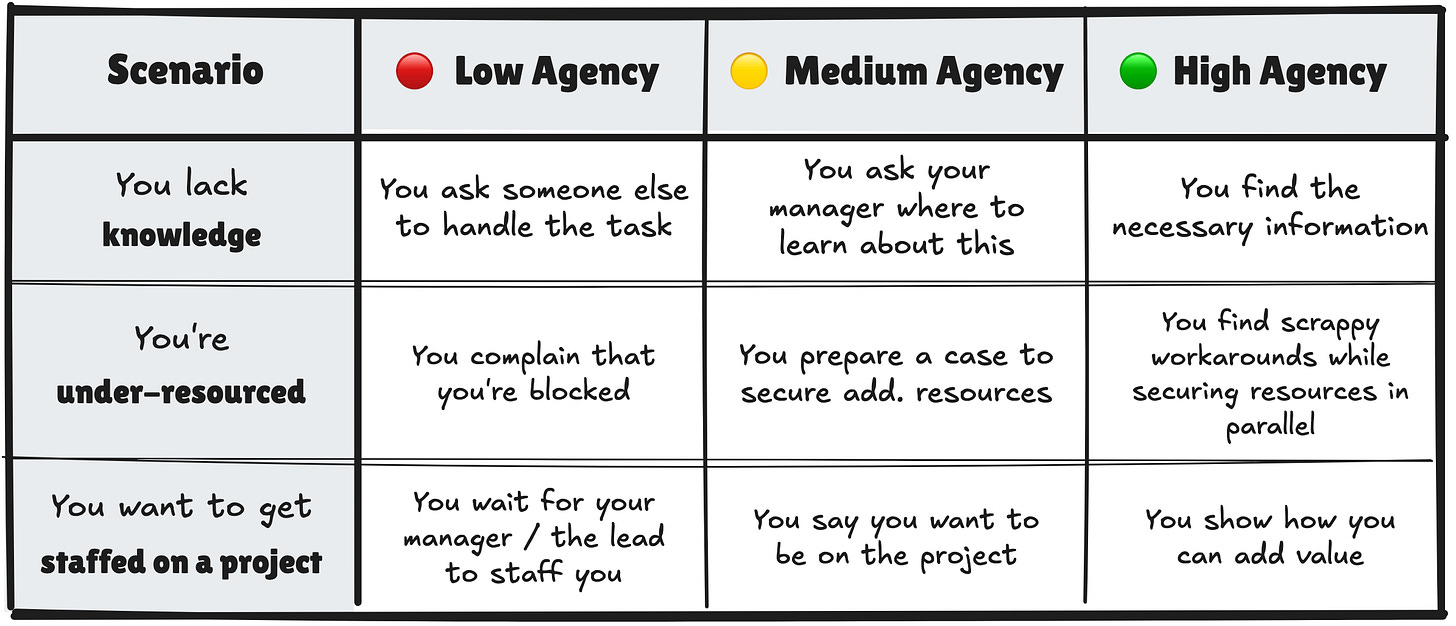

So what does this look like at work?

In the example above, low-agency Lance isn’t really doing anything. He outsources key decisions, is uncomfortable tackling new or challenging topics, and sees himself as a victim of his circumstances.

High-agency Hannah, on the other hand, just gets things done. She doesn’t get discouraged easily, she’s unafraid to make decisions, and she rolls up her sleeves and does what she needs to do — whether or not that’s “her job”.

How to develop agency at work

Every manager wants more high-agency people on their team, and everyone that wants to make an impact and get ahead in their career should strive to increase their agency.

But when I first learned about this concept, I thought: “That’s neat; but how do you actually develop this trait? You can’ just wake up and decide to have more agency, can you?”.

I still think that’s true; simply deciding to change the entire way you approach problems doesn’t do much. But over time, I’ve realized that agency is like a muscle: The more you practice this mindset, the easier it will become.

Once you have the first few “wins” under your belt, you realize that you can, in fact, change things that you thought were out of your control, and solve problems without waiting for someone to assign them to you or give you permission.

At a certain point, it just becomes part of how you operate, and you’ll be able to move an order of magnitude faster than others.

But as is often the case, getting started is the hard part:

How do you spot opportunities to show agency? Sometimes, we’re not even aware we’re in a low-agency mindset, so it’s hard to break out of it

What are concrete examples of high agency in action? Without knowing what it looks like, it’s hard to emulate it

This post aims to help with that. First, we’ll briefly cover three mindset shifts that will help you increase your agency. Then, for the remainder of the post, we’ll go through typical situations at work where people default to a “low-agency” mindset and discuss what you can do instead.

Three core principles for increasing your agency

Before we get into concrete examples in the next section, here are some general mindset shifts I found helpful in developing more agency:

1. Focus on what you can control instead of making excuses

When we feel stuck, there are often legitimate blockers in our way, or adverse circumstances that put us in a difficult position.

It’s understandable to want to give up or complain that things aren’t fair. Maybe somebody told you things were going to be easier than they turned out to be; or, there are other people doing similar things who don’t have to deal with the same challenges.

But we always have two choices: Use the challenging circumstances as an excuse to give up and not do what we planned to do, or focus on the things we can do to make it work.

You’ll be surprised how many ways to move forward you’ll find once you stop thinking about whether the situation is fair, or whose fault it is that you’re in it.

Fred Kofman, author of the book Conscious Business, articulates this well (and I highly recommend reading the full book):

“You are not responsible for your circumstances; you are response-able in the face of your circumstances.” - Fred Kofman, Conscious Business (emphasis mine)

2. Assume you can do anything until proven otherwise

Most people’s default is to assume they can’t do something until they figure out how to do it. The logical consequence is that they don’t even attempt a lot of things because — at first glance — they seem intimidating and beyond their (current) capabilities. And they never take a second, closer look to figure out if that’s even true.

This is one of the most common, and most severe, forms of self-sabotage.

Simply flipping this assumption on its head can massively improve your life, and your career. What helped me with this was realizing that most successful people didn’t get to where they are based on raw talent or intelligence; they got there because they assumed they could change every single thing around them and remove every obstacle in their way — and then they went and did it, even if they initially had no idea how to do it.

“A big secret is that you can bend the world to your will a surprising percentage of the time—most people don’t even try, and just accept that things are the way that they are. […] Almost always, the people who say ‘I am going to keep going until this works, and no matter what the challenges are I’m going to figure them out’, and mean it, go on to succeed.” — Sam Altman, How To Be Successful

In this context, it can be helpful to try not to overthink things. You won’t be able to figure out everything in advance anyways, and with every potential problem you identify your conviction will decrease, making it less likely you’ll see things through.1

Related to this: Be careful not to ask too many people for their opinion too early, or at least don’t take their opinions as fact. People tend to assume anything that hasn’t been done yet cannot be done, and they’ll come up with a million reasons why you’ll fail.

3. Don’t wait for someone to tell you what to do or give you permission

Another incredibly common way to avoid action is to outsource the responsibility to someone else. For example:

You see a problem that you think should be fixed, but doing so would take a lot of effort. So you think “that’s not my problem” because nobody told you to fix it

Or, you put a critical project on hold because one of 12 stakeholders hasn’t explicitly signed off yet

If you wait for others to decide on a path forward, or give you explicit permission, you’re often adding weeks to a project’s timeline; sometimes, you’re even killing it completely.

Not because the idea was bad, but because most organizations are incredibly inefficient at making decisions. If you want to get things done, it’s often best to keep the number of people involved to an absolute minimum, do the thing, and then get everyone else comfortable with the result.

Of course, whether you can get away with this heavily depends on the culture of your company. In some organizations, “just doing things” can get you in trouble, and you definitely shouldn’t go against direct guidance from your manager.

But even in more “sign-off-heavy” cultures there are ways you can unblock yourself; similar to the mindset shift discussed above, you can flip the default here as well.

Instead of waiting until everyone has explicitly signed off, you set a deadline for people to give feedback; after that deadline, everyone is assumed to be in agreement and you move forward. As long as you explicitly communicate this in advance and give people enough time to voice concerns, this often strikes a good balance between making stakeholders feel heard and moving reasonably quickly.

Concrete ways to be “high agency” at work

Alright, let’s get specific. In this section, we’ll cover concrete examples of high-agency behavior across multiple areas:2

Career development

Choosing and structuring work

Handling blockers

Managing projects & stakeholders

In addition to things you can do “the old fashioned way”, I’ll also discuss how you can leverage AI wherever it makes sense. Let’s dive in!

1. Showing agency in your career development

Common complaints from people who feel stuck in their careers are that their manager is not promoting them, or they don’t get any feedback, or they aren’t getting opportunities to take on more responsibility.

In almost all cases, what this means is that nobody is proactively offering these things, not that they asked for them and got rejected.

While it’s true that managers should be doing some of that on their own, simply waiting for this to happen shows a very low-agency mindset.

Nobody cares about your career as much as you do; and if you don’t get what you need from your manager, it’s up to you to take initiative and change that.

That means:

Your manager isn’t giving you feedback?

Schedule a 30-minute feedback session a week in advance, and send your manager a heads-up with a few bullets on what you’d like to discuss. Tons of managers forget to provide feedback regularly, but almost none of them would refuse to give it when put on the spot.

You’re not getting growth opportunities?

Figure out what you want, and share clear goals with your manager. Then, work with them to find ways to move in that direction (e.g. specific projects to be staffed on).

Worst case, they’ll tell you you’re not ready for the kind of opportunity you have in mind; if that happens, push them for concrete feedback and develop a plan to address it. The goal is to either get access to the opportunities you want, or get clarity on where you need to improve to be considered.

Your manager isn’t putting you up for promotion?

Take ownership of the process yourself. Figure out what it takes to get to the next level and work with your manager to identify any gaps, learn about the process and deadlines, and put together a plan. Collect evidence of your readiness for promotion along the way and don’t rely on your manager to compile your promo packet by themselves.

Simply doing solid work and hoping that it gets noticed is not enough.

🤖 How you can leverage AI:

Kicking off the conversation with your manager is an important first step. But if you leave it to them to develop a structured plan, you’ll likely be disappointed.

Instead, give the career ladder or rubric that your company uses for your role to gauge performance by level to AI, together with the feedback you received in the last few review cycles. Then, ask the AI to 1) highlight the key differences between the expectations at your current level and the next, and 2) summarize your main areas for improvement.

Prompt example:

Please review the attached career ladder for a [your role, e.g. Product Manager] as well as the feedback I received during the last performance review cycles.

I'm currently level [X] and want to get promoted to level [Y].

Output the following:

- An executive summary of what it takes to get from my level to the next

- A detailed comparison of what is expected at the next level vs. my current level across each dimension of the career rubric

- A summary of the feedback I have received and how it maps to the role expectations at my current level and the next one

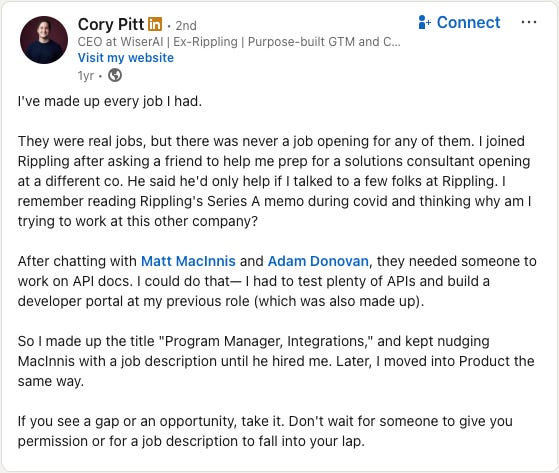

- Suggestions for where I should focus to become "promotion-ready", incl. concrete practical ideas for how I can demonstrate these capabilities. Focus on one or two key themes rather than a tactical laundry list.You want a role that doesn’t exist?

Invent it and pitch it.

It might not always work out, but if it does, you have the opportunity to write your own job description, and you’ll be the first (and potentially only) applicant.

2. Showing agency in how you approach your work

Over the years, I’ve managed a number of different teams; some of these I “inherited”, others I built from scratch.

And while every company, team, and person I worked with were unique, there has been a consistent goal across all of these: Increasing agency.3

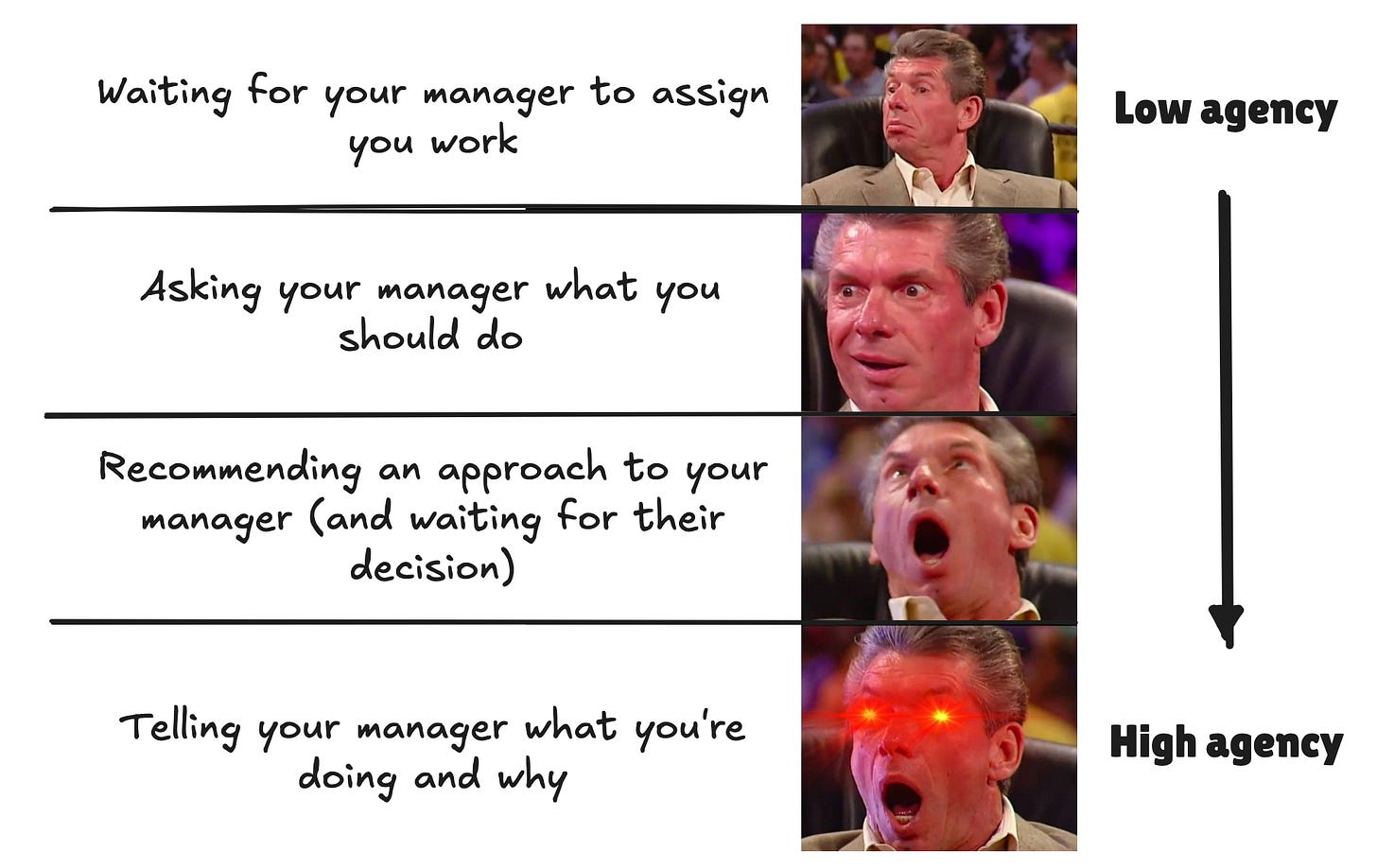

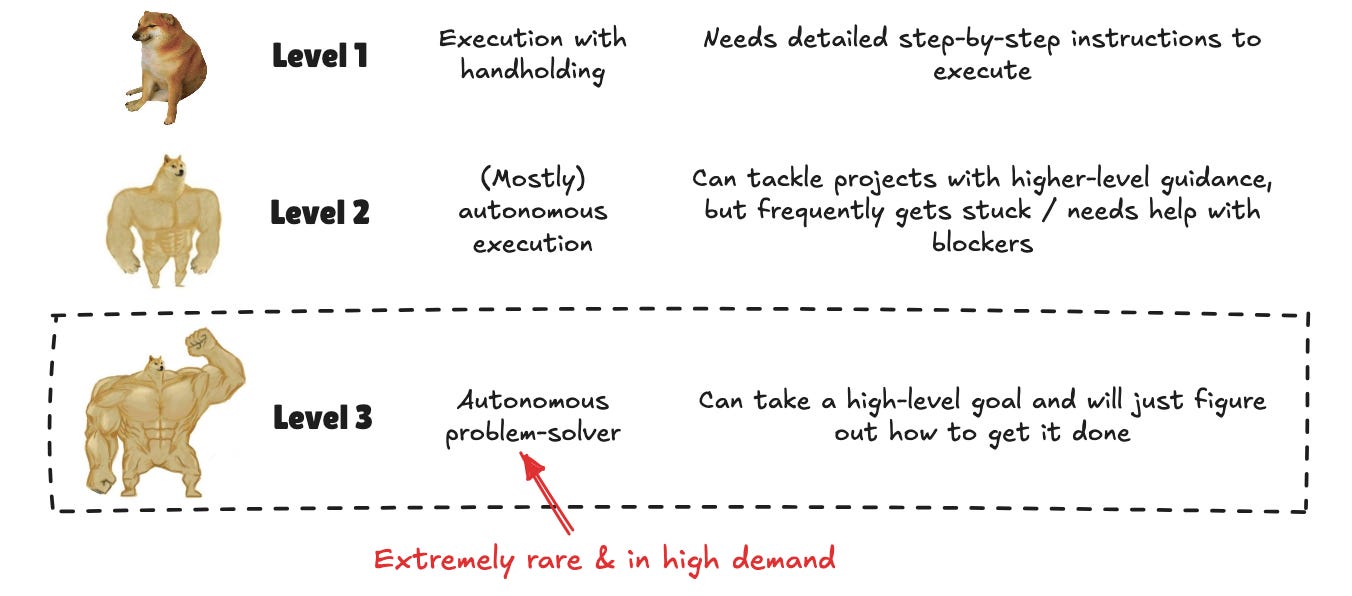

From a manager’s perspective, there are essentially three “levels” of ICs:

Most people early in their careers start at Level 1. That’s natural; without a lot of experience, you typically lack the confidence to make judgment calls and figure things out for yourself.

But moving to Level 3 should be the explicit joint goal of any (ambitious) IC and their manager. Getting there is a win-win:4

💼 For the manager, it frees up bandwidth so they can spend more time making sure the team is working on the right things, has enough resources, works well with other teams etc.

🛠️ For the IC, it means having the freedom to solve problems creatively instead of feeling micromanaged and just executing orders. And you’ll be much less likely to get replaced by AI: AI can already execute straightforward tasks with detailed instructions well, but is (so far) unable to take a high-level goal and run with it

Unfortunately, this transition is hard. The more hands-off the manager is, the more ambiguity there is that the IC needs to push through. Being a high-agency IC means 1) trusting you’ll figure it out and then 2) pushing relentlessly to do just that.

Here are some behavioral shifts that can help you move in the right direction:

Get sign-off on your approach instead of asking what to do

If you don’t do any work unless your manager tells you to do something, you’re essentially asking to be micromanaged.

Asking your manager what to do is only slightly better; you’re proactively signaling that you’re idle and want to get started, but you’re not taking the initiative to figure out what needs to get done. You’re still asking your manager to do all of the heavy lifting.

Instead, tell your manager what you intend to do and give them an opportunity to provide input. Ideally, you already start executing while you’re waiting for a response (that, depending on how busy your manager is, might never come).

That way, you’re removing your manager as the bottleneck while still giving them an opportunity to weigh in.

🤖 How you can leverage AI:

In order for this approach to actually remove friction, you need to make sure that you give your manager sufficient information so that in most cases they will simply respond along the lines of “sounds good to me” instead of hitting you with a barrage of questions.

The easiest way to achieve this is to ask AI to review your approach and anticipate likely questions or concerns your manager will have. Then, you can proactively address them in your message.

Prompt example:

<goal> I'm about to send my manager an update re: a project I'm working on. Please review 1) the project context below as well as 2) my draft message and highlight any questions or concerns they might have (so I can proactively address them). </goal>

<context>

- [Either add context on your project here, or attach relevant documents (e.g. project plans, meeting notes etc.)]

- [Paste your draft message to your manager here or attach it as a document]

</context>

<output> In addition to a list of questions or concerns my manager will likely have in response to my update, please also provide a proposed edit of my message (add placeholders in the message wherever I need to insert additional context or information you don't have before sending it out). </output>Note: This works especially well if the AI has context on who your manager is and how they think. You can achieve that by creating a Project (e.g. in ChatGPT or Claude) and uploading past questions and feedback you’ve gotten from your manager and then using this Project to run the prompt above.

Figure out how to make something work instead of finding reasons why it won’t

A lot of people, especially in larger organizations, love to point out reasons why something won’t work instead of trying to figure out how to make it work.

I think people do this because:

They think it makes them look smart to point out every risk, shortcoming, and challenge, and

Because it helps them cover their ass.

Getting something done means you have to take a stance and push through obstacles. If things don’t work out as planned, most people prefer to be the one that says “I told you so” instead of the one that put their personal reputation behind the failed effort.

However, this risk-minimizing approach will only get you so far. In high-performance organizations, you are ultimately not judged by how few mistakes you made, but rather by the level of impact you realized. So while constantly playing devil’s advocate might give you job security in the short term, it will severely limit your career trajectory in the longer term.

When faced with a new task, assume by default that it can be done, and pretend you have to do it; how could you make it work? Consistently practicing this mindset is one of the easiest ways to stand out.

Bonus points: Proactively identify problems and opportunities

Doing the things discussed above is already a solid start. But you can take it one step further: Instead of waiting for someone to hand a project or problem to you, pay attention and proactively spot opportunities to either unlock additional growth or improve efficiency.

The more senior you get, the more the expectation will be that you “own” an area of the business and help decide what work is worth doing. Practicing this even when it’s not officially part of your job description yet is a great way to show you’re ready for more responsibility.

🤖 How you can leverage AI:

I don’t recommend outsourcing this process of identifying opportunities to AI, as it doesn’t have enough business context to do a good job here.

However, once you find something that seems promising, you can use AI to size the opportunity and pitch it to your manager.

Just attach a document with notes on the opportunities you identified and add some context on your company so the AI can provide a customized sizing framework.

<goal> I have a list of opportunities that I identified across the company. I want to size their potential impact to figure out which ones should be prioritized. Your job is to help me put together a structured sizing framework for each one. </goal>

<context> [Add context on your company, team etc. here] </context>

<output> The framework you output should specify what metric can be directly impacted by the work stream, and establish a connection to a topline metric (e.g. Daily Active Users, Revenue etc.; this will be the ultimate business impact we can use to compare initiatives). Provide the calculation and list out the data that needs to be plugged in; in addition, provide benchmarks from comparable companies in case I cannot pull some of the data from our internal systems </output>3. Showing agency in how you handle blockers

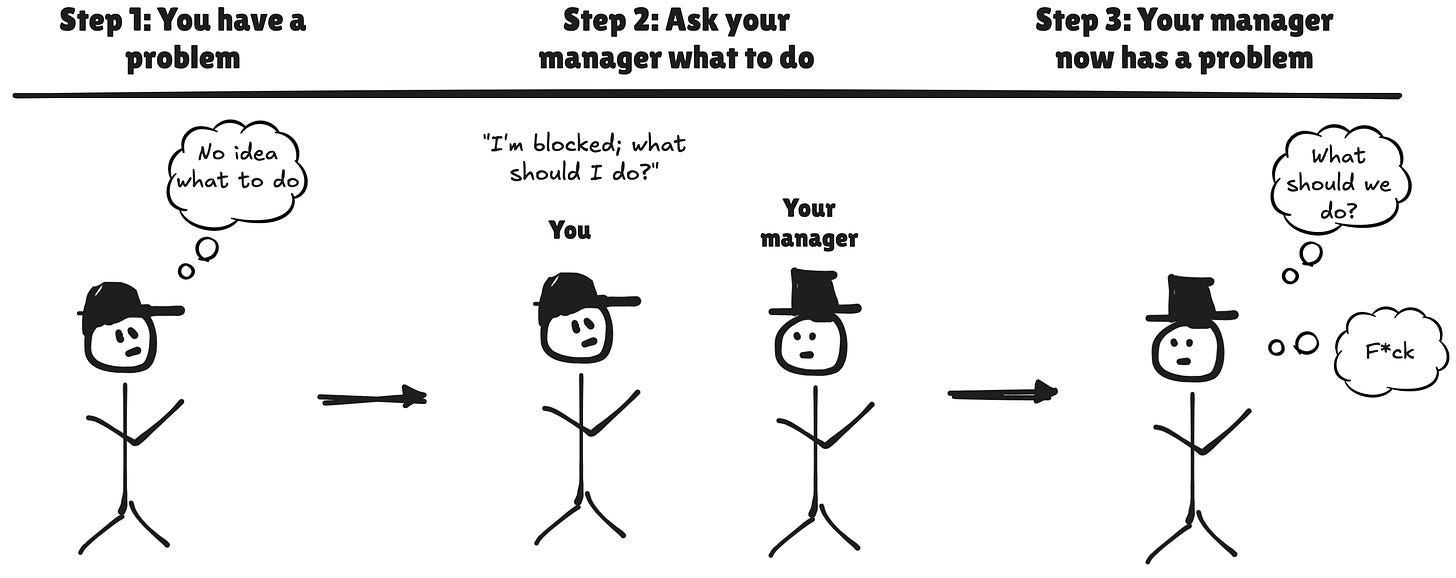

A classic symptom of someone with a low-agency mindset is that the moment something blocks their progress, they jump on the “excuse” to stop working. Progress is out of their hands; before they can move forward, someone else needs to unblock them.

In most cases, they either look to their manager or other teams for that.

To be clear, this is a very natural reaction to running into friction, and I’ve been there plenty of times myself. But these moments are the ideal opportunities to practice agency, and learning to unblock yourself will pay massive dividends. You’ll be able to move much faster, and your manager will love you for not trying to pass the monkey to them every single time something comes up.

Raising your bar for what constitutes a blocker

Many people consider themselves blocked when they can’t proceed with a project as planned. But that’s just a complication, not a blocker. There are usually multiple ways to get to a desired outcome, and just because your first attempt didn’t work out doesn’t mean you’re out of options.

Only once you’ve exhausted all of the options available to you, you are actually blocked and need somebody else’s help. Which brings us to the next point:

Reduce your reliance on other teams

A lot of the time when people on my team have told me they’re blocked, it’s been some version of “We’re waiting on this other team to do something and can’t move forward until they do”.

This seems like a neat excuse: You can’t move forward, but it’s not really your fault. However, not all dependencies on other teams are immutable things you just have to accept.

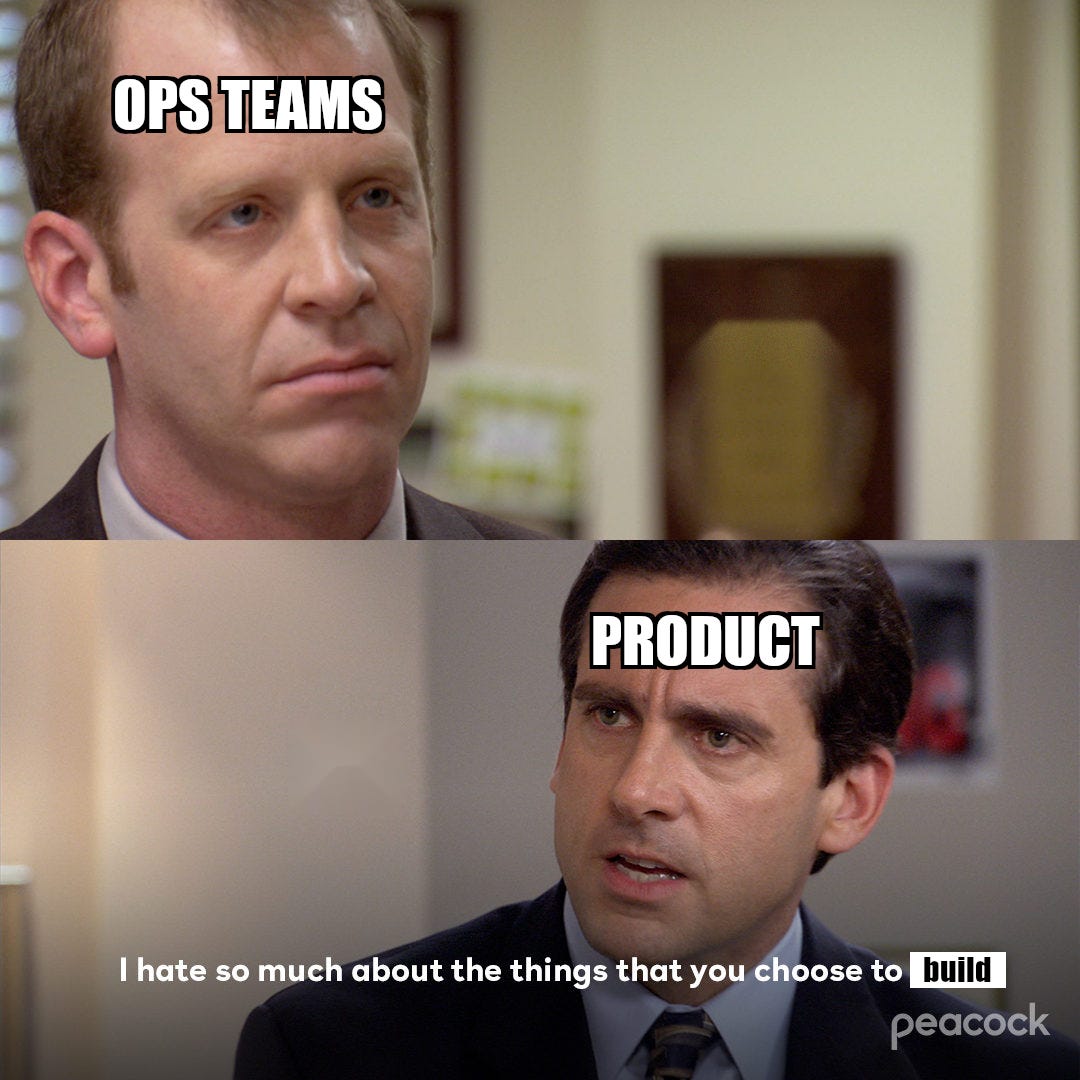

For example, when I was at Uber, the Operations teams managing the reliability of the marketplace on a day-to-day basis often felt blocked by the Product team.

How are you supposed to avoid reliability dips during bad weather if the real-time pricing algorithms don’t take this signal into account? Product should fix this ASAP!

Our tooling doesn’t allow us to target incentives at specific restaurants? Nothing we can do for McDonald’s reliability until Product builds this capability, I guess!

The best Ops managers, however, didn’t just throw up their hands in defeat and blamed Product. Instead, they implemented hacky band-aid solutions; for example, to address the pain points above, people built:

A semi-automated process to pull in near-term weather forecast data, generate incentive recommendations, and send comms to couriers

A Python script that created restaurant-level geofences so Uber’s geofence-based incentive system could be used creatively to boost specific restaurants

Note that this wasn’t done by engineers; these were people from non-technical backgrounds who learned basic SQL and Python to unblock themselves.

This high-agency approach had two benefits: Besides unblocking the business, it also created an incentive for the Product org to act faster. The hacky proof of concept showed that there was a real business case while the brittle nature of these band-aid solutions made Product highly motivated to replace them with something more robust.

🤖 How you can leverage AI:

Back when these challenges came up at Uber, AI wasn’t nearly where it is today. I.e. we had to build these things by hand.

Now, with AI, this has become an order of magnitude easier. Instead of learning Python, you can just ask an LLM to code up a simple tool. As long as you’re just using it for internal processes, it matters less whether it’s production-ready code.

Anticipate blockers and bottlenecks

The best way not to get blocked is to anticipate bottlenecks in advance.

Most people focus only on their part of a project and see everything else as “not their problem”. Unfortunately, parts owned by other people often become your problem at some point if you don’t manage dependencies proactively.

You might be reliant on inputs from other teams? Then you need to scope out what those will be, and agree on the exact things that the other team will deliver (and deadlines for doing so)

Your work needs to be reviewed, processed, or ingested by another team? Connect with them and align on the specifics so you can bake this into your plan

Don’t just trust that somebody else will be on top of these things; more often than not, you’ll find that nobody took the initiative.

4. Showing agency by just doing things

Agency influencers (yes, that’s a thing) love to repeat “You can just do things!”.

They’re right; you can (I checked!). And yet, many people seem to think their job is to just call meetings, send emails, and talk about things without ever actually doing anything.

Here’s how to stand out by going against this trend:

Put pen to paper

Sometimes, work can feel like you’re playing a game called “How many meetings can we have about a topic without reaching a conclusion?”.

In my view, one of the key reasons this tends to happen is because complex topics are hard to solve in your head. Somebody brings up a new consideration, another person revisits a point that you thought was already decided, and the discussion just keeps going in circles.

The easiest way to prevent this (but a heavily underutilized one) is to just put pen to paper. Here are a few concrete things you can do:

If it’s a complex decision and many teams are involved, consider putting down clear roles and responsibilities

Put forward an issue tree or decision framework that structures and simplifies the problem. Or, make a concrete recommendation that people can react to. Either way, it will be much easier to iterate on something concrete

Document every decision that has been made, whether big or small. That way, you don’t keep reopening the same topics

🤖 How you can leverage AI:

With AI, mock-ups often take less time to build than it takes to write up a doc describing what you have in mind.

And since they give people something tangible to react to, they’re much more effective. When five different people read a proposal, they imagine five slightly different things since they’ll fill in the gaps based on their priors and expectations. With a mock-up (or prototype), you remove that ambiguity.

I recommend to get started with static (or slightly interactive) mock-ups. Both ChatGPT and Claude are great choices:

ChatGPT if you want high-quality results fast

Claude if you plan to iterate a lot (as the Artifact system makes this very convenient)

Often, this type of mock-up is enough to get stakeholders on the same page. If you want to flesh things out into a proper prototype, however, you can move over to a dedicated vibe coding / prototyping tool. I personally like Vercel V0; you can get something reasonably pretty and robust fairly quickly, and deploy it with one click to share it with others.

If there’s no clear owner (and you need it done), do it yourself

In one of my previous jobs, we’d been using the same take-home exercise for interviews for years. It was outdated, had been leaked online, and everyone agreed that it should be updated.

But for months, nothing happened. Everyone just… waited. For what? Who knows; maybe for someone else to take the lead, or for leadership to give top-down guidance.

Eventually, I just blocked off an afternoon and created a new exercise. It didn’t actually take that long; the difficult part was getting over the inertia and feeling of “That’s not my job”. What’s more, I’m pretty sure it was much more efficient this way compared to an “official” revamp where every team would have wanted to weigh in on what the exercise should look like.

Note: Of course, you’ll want to do this selectively only for things you care about a lot. Otherwise, you’ll quickly become the go-to person for every “unwanted” task in your org.

Just do small tasks instead of delegating them

I keep a mental “hall of shame” of the most ridiculous things I’ve seen people delegate over the years.

They range from “Can someone please rename this Slack channel?” to “Can you add Tom to the meeting invite?” or “Can you change the slide title from [X] to [Y]?”.

What do all of these tasks have in common? Writing out the ask took longer than just doing the thing itself. Regardless of whether you’re a project manager, Director, or VP: The only thing that delegating this kind of task accomplishes is increasing the (negative) corporate vibes of your culture.5

And while we’re at it: If you do delegate, address your request to a specific person. “Can we…” or “Can someone…” is a surefire way to trigger diffusion of responsibility; nobody will feel responsible, and it won’t get done.

Closing thoughts

Agency can be learned.

Some people might be born with more of it than others, but that doesn’t mean you can’t build this muscle over time. The important first step is to recognize when you’re showing a lack of agency; then, you can practice brainstorming (and executing) high-agency ways to deal with the situation.

If you do this diligently for a while, it’ll become second nature; and your career will take a different trajectory.

Obviously, that’s not to say planning, or thinking things through, is never a good idea. But the value of it varies greatly depending on the situation. For example, deeply thinking about the premise of your business venture, or side hustle, or project at work (and gathering data, e.g. from interviewing potential customers) makes sense; the more fully-formed your thoughts are in this regard, the stronger your conviction will be that you’re working on a problem worth solving. But thinking too much about all of the operational considerations of executing the idea and what could go wrong is counterproductive; e.g. if Travis Kalanick had obsessed over the difficulties of scaling Uber in hundreds of cities with hostile regulatory environments, he’d never have started the company.

Note: The idea isn’t that you treat this as a rigid blueprint for what to do; after all, just following instructions is kind of the opposite of agency. But hopefully, these tangible examples will give you some ideas on how to get started and will help you look at problems from a different angle.

Initially, I wasn’t familiar with the concept and therefore didn’t have a word for it. But in hindsight, I realized that’s exactly what I was trying to hire for and promote

Of course, not every manager actually wants this in practice. If your manager is too insecure to give their direct reports freedom to operate like this, there is only so much you can do (agency or no agency); at least while you’re staying on that team. The high-agency move, in that case, would be to find a team where you’ll get more autonomy

This is mainly targeted at delegation requests via email or Slack (as in those cases you’re clearly at your laptop and could just do the thing). If an exec makes a request like this in passing in the hallway, it might be legitimate; sometimes, they don’t really get to open their laptop and do anything for quite some time if they’re stuck in back-to-back meetings.

I love this my only add is mostly a warning to women. DO NOT USE THIS AGENCY FOR TASKS THAT REQUIRE DOMESTIC LABOR AT WORK. Do not sign up to take agency on getting people to sign Tom's birthday card or cleaning up the station at the kitchen counter have been delivered. I've seen so many high agency women reduced to fancy maids and secretaries. Solve for the business drivers first.

Absolutely love this. Great newsletter today.